Théories et pratiques de l’apprentissage situé 25/101

Cognition in practice (9/n)

Introduction

Dans cette section du chapitre “Psychologie et anthropologie II » de son livre « Cognition in Practice », Jean Lave s’attaque aux sources des problèmes qui se renforcent mutuellement. Jean Lave énonce des hypothèses sur lesquelles reposent les grandes divisions en termes d’épistémologie positiviste .

épistémologie commune

I have yet to discuss the sources of the coherence with which the issues reinforce one another.They take their shape, the great divides are formed, in terms of a positivist epistemology which specifies a series of assumptions on which they are based: rationality exists as the ideal canon of thought;

experimentation can be thought of as the embodiment of this ideal in scientific practice; science is the value-free collection of factual knowledge about the world; factual knowledge about the world is the basis for the formation of scientific theory, not the other way around; science is the opposite of history, the one nomothetic the other ideographic; cognitive processes are general and fundamental, psychology, correspondingly, a nomothetic discipline; society and culture shape the particularities of cognition and give it content, thus, sociocultural context is specific, its study ideographic; general laws of human behavior, therefore, must be dissected a way from the historical and social obfuscations which give them particularity.

Puis elle souligne que ces propositions (hypothèses) s’impliquent mutuellement de manière complexe. Remettre en question l’une d’entre elles, c’est remettre en question toutes les autres. Et, par conséquent, pour Jean Lave, la quête d’une meilleure compréhension de la cognition de tous les jours, est, de manière inévitable,une question épistémologique fondamentale.

« These propositions entail one another in complex ways. To challenge anyone of them draws the rest into question as well. A quest for better understanding of everyday cognition in context that questions conventional relations between the socially organized world, culture and cognition – and hence the whole field of assumptions – is unavoidably, therefore, a fundamental epistemological question. »

Pour Jean Lave, il est utile de s’interroger et passer en revue les differentes conception de l’ordre social et des relations des individus à cet ordre pour une meilleure compréhension des relations entre culture et cognition.

« To understand better the relations between culture and cognition implied in the shared epistemology of positivistic cognitive studies (whether in anthropology or psychology), it may be useful to reviewcentral features of the conception of social order and the relations of individuals to that order. »

La théorie du fonctionnalisme normatif, nous dit Jean Lave, suppose un ordre social qui fonctionne à l’équilibre. Les individus sont moulés et formés par un processus de socialisation qui les amènent à se conduire selon de rôles et des pratiques régies par des normes. La société est considéré comme extérieure à l’individu, avec une existence séparé de celle des individus qui la traversent.

Normative functionalism, from Durkheim and Wundt to Parsons and cognitive studies today, posits a functioning social order in equilibrium, and individuals molded and shaped through socialization into performers of normatively governed social roles and practices. Society is conceived of as external to the individual, having a separate (and for experimental purposes separable) existence from the individuals who pass through it.

La théorie du fonctionnalisme normatif situe la relation entre culture et cognition dans l’esprit de l’individu, dans la mémoire et l’accumulation d’expériences de socialisation passées (…) les changements nécessitent du temps.

It locates relations between culture and cognition within the mind of the experiencing individual, in memory and in accumulation of past socializing experiences. Change in the character of society and of mind is conceived of as an evolutionary matter requiring sweeping time spans.

Ainsi, quand l’étude est limité à la durée d’une vie humaine, ou de manière plus restreinte à l’enfance (…) les pratiques cognitives, la société et la culture sont considérées comme constantes.

« Thus, when the investigation is confined to a human lifespan or more narrowly, childhood, or even more narrowly, current cognitive practices, society and culture are assumed for all intents and purposes, to be constant. »

Dans ce schéma, la culture est assimilée à une connaissance factuelle accumulée

« Culture, in this scheme, is equated with accumulated factual knowledge, increasing in individuals andsocieties alike with the evolutionary move toward individualism and all that goes with it. Durkheim laid out the position generally current at the turn of the century (1915; Durkheim and Mauss 1963). Its contemporary guise requires elucidation. »

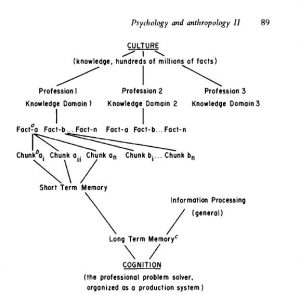

Selon les spécialistes des sciences cognitives, l’expertise dans un “domaine” de connaissance donné représenterait 50000 “morceaux de connaissance (…) et une culture de 100 à 10000 fois ce qu’une personne connait.

NOTA: Jean Lave, met “domaine” entre guillemets car elle ne croit personnellement pas à leur existence, en soi.

Cognitive scientists discuss expertise in a particular knowledge « domain » e.g. chess, as on the order of 50,000 chunks of knowledge (Simon 1980: 83-84; Norman 1980; originally formulated in Simon and Barenfeld 1969). Anthropologists with an interest in cognitive science have incorporated this quantitative formulation into longstanding views of culture as accumulated knowledge (Roberts 1964; 0′ Andrade 1981; Romney, Weller and Batchelder 1986). D’Andrade extrapolates from 50,000 chunks of knowledge in an area of professional expertise (note the emphasis on professions/occupations here as elsewhere in discussions of modes of thought), to the person who might have several hundred thousand to several million chunks of information, to the information pool- the culture – of a society (a hundred to 10,000 times what a person knows.)

Après avoir représenté la relation entre cognition et culture qui découle de cette vue, Jean Lave ouvre une autre piste pour essayer d’élucider l’absence de prise en compte du contexte dans l’activité cognitive.

We must look elsewhere for the – absent – social context of cognitive activity.ll It is conceived of in terms that have not changed in a surprisingly long time, surprising because even the revolution of information processing psychology away from behaviorism did not lead to a reformulation of relations between the person and the object world; relations between cognition and its « environments » are still treated in terms of stimuli which evoke responses. Neisser (…] has suggested that information processing psychology is merely what goes on in between. It follows that social context is, in this theoretical position, both separated from, and in a deterministic relationship with, cognition, such that (were activity in the world ever the object of study) apparent variation in the deployment of cognitive processes would in the end necessarily be interpreted in terms of what « naturally » varies – the particulars of socially, culturally organized situations. »

Jean Lave voit dans la création d’expérimentations non contextualisée que l’on trouve en psychologie un moyen de repousser toute question relative aux interrelations entre pensée et contexte social. (…) ce qui permet de s’affranchir de toute position théorique concernant la relation entre le monde social et l’activité cognitive. L’accent étant mis sur le caractère uniforme des processus psychologique.

The privileged « non-context » of experimentation has been a major device within psychology for relegating issues about the interrelations of thinking and social context, and in particular the hegemonic character of the world-around, to the status of the residual and implicit. But to conduct the practice oflaboratory psychology « as if » experiments had no sociocultural context does not correspondingly exempt that practice from a general theoretical position concerning relations between the social world and cognitive activity.Emphasis on the fundamental, uniform nature of psychological processes, with concomitant assignment of variability to a particular configuration of the social world, is a position, one which asserts the hegemony of the latter.

Et si les problèmes de conception de la cognition en relation avec le monde social naissent de leur séparation artificielle, les relations entre culture et cognition souffrent de la difficulté opposée. Culture et connaissance sont assimilées l’une à l’autre

« If problems with conceptions of cognition in relation with the social world stem from their artificial separation, relations of culture and cognition suffer opposite difficulties. Culture and knowledge are equated with each other… »

La mémoire jouant un rôle de stockage des acquisitions culturelles, toute connaissance générale est vue comme une encyclopédie bien indexée.

« Memory takes on the character of a place where cultural acquisitions are stored, and where development toward increasingly integrated and « rational » general knowledge is to be expected. Simon’s (1980) equation of expert knowledge with a well indexed, easily accessible, encyclopedia provides an excellent example. The same metaphor has currency in developmental psychology. »

La difficulté principale provient du fait que la relation cognition/culture n’est jamais construite au présent, et considère qu’elle doit son existence à des événements passés. … Et ainsi de définir la culture comme « ce que les gens ont acquis et transporté dans leur tête” plutôt comme la relation immédiate entre des individus et l’ordre socio-culturel dans lequel ils vivent.

« The main difficulty with this view is that the nexus ofcognition/culture relations is never constructed in the present, but always assumed to have an existence because of events which took place in the past. « Warehouse » and « toolkit » metaphors for the location of culture in memory make it possible to abnegate the investigation of relations between cognition and culture by, in effect, defining culture as « what people have acquired, and carry around in their heads, » rather than as an immediate relation between individuals and the sociocultural order within which they live their Iives. »

Dans la pratique, cela signifie que cela a permis aux chercheurs cognitivistes d’affirmer le rôle important de la culture dans la cognition sans aller au-delà de l’unité élémentaire d’analyse – le « processus cognitif » d’un individu particulier en réponse à une tâche effectuée en laboratoire (NOTA : et pas dans la vraie vie). Cette approche ne permettant pas d’expliquer les relations, entre personnes-en-action et le monde social autour d’elles.

« In practice this has meant that cognitive researchers have been able to proclaim the important role of culture in cognition without looking beyond the standard unit of analysis: the « cognitive processes » of a particular individual in response to a laboratory task. But this approach provides no basis for accounting for relations, especially generative relations, between people-in-action and the social world around them. »

Pour Jean Lave, la question de la culture comme accumulation de connaissances et l’esprit et culture considérées comme deux aspects d’un même phénomène ont prédominé au cours du siècle précédent (19eme), Ce qui pose, dit-elle un problème crucial, l’obligation de les attribuer au même lien dans le monde social.

The view that culture is the evolutionary accumulation of knowledge along with increasingly complex technology and social forms, and mind and culture but two aspects of the same phenomenon, has prevailed in cognitive theory through most of the last century

A crucial problem has emerged from this sustained equation of culture and cognition. If culture and cognition are treated as aspects of a single phenomenon, they must both in the end be allocated to the same nexus in the social world.

Deux possibilités se présentent immédiatement à l’esprit

La première, très largement représentée chez les psychologues cognitivistes – fusionne culture et cognition en représentations dans l’esprit

« The first, heavily represented among cognitive psychologists, collapses culture and cognition into representations in the mind (cf. Minick 1985). The concept of « culture » is simply transformed into that of « knowledge, » and culture dispensed with altogether . »

La seconde, très largement représentée chez les anthropologues, loge la culture et la cognition dans un système de signification supra-organique, un pool d’information ». Dans ce cas, les structures culturelles telles que le langage deviennent des constructions réifiée, mais la cognition, en tant que processus génératif individuel est oublié dans l’équation.

The second, heavily represented in anthropology, locates culture and cognition together by transforming them into a superorganic system of meaning, « an information pool. » In this case cultural structures such as language become reified constructs, but cognition, as an individual generative process, drops out of the equation. Neither appears to offer a satisfactory solution.

Ni l’une ni l’autre n’offre une solution satisfaisante.

De plus, la fusion du terme culture avec le concept de connaissance fait que le terme « culture » est traité par la position fonctionnaliste comme une entité sociale, grande, avec des limites et non théorisable, comme une société

« Further, having merged culture into the concept « knowledge, » the functionalist position treats the term « culture » as if it referred to somelarge, bounded untheorizable, particular social entity, a society. »

Pour Jean Lave, cette confusion dans les catégories d’analyse, a comme malheureuse conséquence de ne pas permettre de démêler l’ordre socioculturel de l’expérience que l’individu en a.

(The) unfortunate consequence of these confusions of analytic categories is to reduce any unit of analysis which insists on the integral nature of individual cognition and its context, to a component, a literal subunit of the society (culture), leaving no basis for disentangling the sociocultural order from the individual’s experience of it.

Problème auquel Jean Lave ne voit pas d’issue/

Further conceptual elaboration of these categories seems unlikely so long as the culture-knowledge-society terms are used in the conftated fashion just described.

Un dernier problème avant les conclusions (qui feront l’objet du prochain billet)

Le problème qui fait partie d’un ensemble de pratiques plus large des pays développés (Western) qui consiste à transformer en termes idéologiques ce qui est considéré comme commun et « normal » en naturel, de le biologiser.

« There is one further problem concerning the treatment of culture in cognitive research, in this case as part of much broader Western cultural practices. Sahlins argues that it is characteristic of this social formation, perhaps uniquely, to transform in ideological terms that which isculturally commonplace and « normal » into the natural, to biologize it. »

Vus à cette lumière, les « processus cognitifs » font de bons candidats pour être réexaminés en tant que phénomènes constitués culturellement. La théorie cognitive pourrait être analysée comme un mode par lequel le culturel est ainsi « naturalisé »

« Cognitive processes, » viewed in this light, become obvious candidates for reexamination as culturally constituted phenomena. Cognitive theory might then be analyzed as a mode by which the cultural is so « naturalized. »

Billets précédents

Billet 1: Définitions de l’apprentissage situé

Billet 2: Pourquoi s’intéresser à la théorie de l’apprentissage situé?

Billet 3: Démarche et retour aux sources

Billet 4: Mai 1968 et l’apprentissage situé

Billet 5: Apprentissage situé et conversation

Billet 6: Lucy Suchman, mon téléphone portable et moi

Billet 7: Conversations avec moi-même (n° 1)

Billet 8: L’apprentissage situé mis en pratique, cela ferait quoi?

Billet 9: Contribution de la psychologie soviétique à la théorie de l’apprentissage situé

Billet 10: Les apports de la philosophie à la théorie de l’apprentissage situé

Billet 11: Focus sur l’école Dewey

Billet 12: Apports de la psychologie de la perception – la notion d’affordance

Billet 13: Apprentissage situé et intelligence artificielle, deep learning, réalité virtuelle, réalité augmentée, etc…

Billet 14: Conversations avec moi-même (N°2)

Billet 15: Quand John Dewey rencontre Jean Lave

Billet 16: Cognition in Practice (1/n)

Billet 17: Cognition in Practice (2/n)

Billet 18: Cognition in Practice (3/n)

Billet 19: Cognition in Practice (4/n)

Billet 20 : Cognition in Practice (5/n)

Billet 21: « Conversations avec moi même N°3 »

Billet 22: Cognition in Practice (6/n)

Related Posts

Apprendre au 21e siècle (Partie II)

Codéveloppement à haute vitesse 12/n

Codéveloppement à haute vitesse 9/n

Articles récents

Archives

- mai 2024

- mars 2024

- janvier 2024

- décembre 2023

- septembre 2023

- juin 2023

- avril 2023

- mars 2023

- janvier 2023

- octobre 2022

- septembre 2022

- juillet 2022

- mai 2022

- avril 2022

- mars 2022

- février 2022

- janvier 2022

- octobre 2021

- août 2021

- juillet 2021

- mai 2021

- février 2021

- juin 2020

- mai 2020

- avril 2020

- février 2020

- janvier 2020

- décembre 2019

- novembre 2019

- octobre 2019

- septembre 2019

- août 2019

- juillet 2019

- mai 2019

- avril 2019

- mars 2019

- février 2019

- janvier 2019

- décembre 2018

- septembre 2018

- août 2018

- juillet 2018

- juin 2018

- mai 2018

- avril 2018

- mars 2018

- février 2018

- janvier 2018

- décembre 2017

- novembre 2017

- octobre 2017

- septembre 2017

- août 2017

- juin 2017

- mai 2017

- avril 2017

- mars 2017

- février 2017

- janvier 2017

Catégories

- Actualités

- Adaptive Learning

- Allemagne

- Apprendre

- Apprentissage

- Branding

- Business

- Coaching

- Codeveloppement

- Communautés de pratique

- Deep learning

- Design

- Development

- E-Learning

- Ecole

- Education

- Europe

- Formation

- IA

- Intelligence articificielle

- LBC

- metacognition

- Non classé

- Orientation

- orientation

- Philosophie

- Poésie

- Réalité Augmentée

- Réalité Virtuelle

- Transition digitale

- WOL

Commentaires récents