Théories et pratiques de l’apprentissage situé 47/101

Cognition in Practice 27/n

Introduction

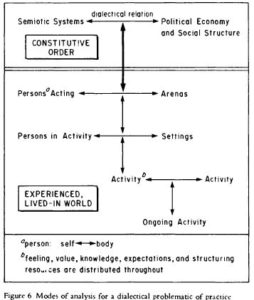

Dans cette section du dernier chapitre de son livre “Cognition in Practice …” Jean Lave , souligne que culture et cognition appartiennent à des niveaux différents de l’ordre socioculturel et nous propose un schéma présentant différents modes d’analyse d’une problématique de pratique dialectique (Modes of analysis for a dialeclical problematic of praclice)

Culture,cognition et l’ordre socioculturel

La cognition, nous réaffirme Jean Lave, est située (located) dans le monde au travers d’une activité dans un contexte. A l’opposé, la culture est un aspect de l’ordre constitué. Vus ainsi, la culture et la cognition appartiennent à deux niveaux différents de l’ordre socioculturel.

« However one defines cognition, it surely would be located, in this scheme, in the experiencing of the world and the world experienced, through activity, in context. Culture, on the other hand. is an aspect of the constitutive order.

In such a view, culture and cognition belong to different levels of the sociocultural order and address each other neither directly, nor in isolation from their entailments with other aspects, respectively, of the constitutive order and the lived-in world. Something like this view of social order must, I think, underlie a theory of persons-acting, engaged in everyday activity in context. »

Si l’on revient, à la lumière de cette conclusion, sur les racines culturelles et historiques de la rationalité et de la théorie cognitive, … sur les travaux d’Adorno, Sahlins et Bourdieu, et leur affirmation que « Les systèmes culturels et leurs implications structurelles, en tant qu’aspects d’un ordre constitutif particulier, motivent l’expérience et sont des ressources utilisées pour façonner l’activité intentionnelle dans le monde vécu. »

« We may reconsider, in the light of this conclusion, the significance of the previous argument about the cultural and historical roots of rationality and cognitive theory. The work of Adorno, especially, and more recently that of Sahlins and Bourdieu, explores what have just been characterized as entailments of meaning and structure within the constitutive order. Their discussions of the foundations of the Western ideology of rationality are not about the nature of cognition, activity orexperience as such. Instead, they claim that cultural systems and their structural entailments, as aspects of a particular constitutive order, motivate experience and are resources drawn upon in the fashioning of intentional activity in the lived-in world. »

Le schéma 6 propose une représentation résumée des relations analytiques centrales dans la problématique de l’ordre constitué et du monde vécu au travers de l’experience

Figure 6 provides a summary of analytic relations central to the dialectical problematic of constitutive order and the experienced livedin world.

Trois modes généraux d’analyse

As a method for the investigation of practice it recommends three general analytic modes:

1. Analyse des systèmes sémiotiques

d’abord, une analyse des systèmes sémiotiques avec leurs implications structurelles.

First, an analysis of semiotic systems with their structural entailments. This has been exemplified here in the discussion of relations among systems of belief and social institutions, for example, the meaning of rationality in its relations with commoditization and the institutionalization of cognitive theory in schooling. « Culture » is appropriately brought into analyses of its experienced realization in this complex, entailed form.

2. Une analyse de la cognition vue comme une partie d’une théorie de la pratique, par l’exploration des relations entre personnes-en action (person-acting) cadre (setting) et activité.

Secondly, and correspondingly, an analysis of cognition must be constituted as part of a theory of practice, in explorations of the relations among person-acting, setting and activity.

3. le troisième mode d’analyse est celui d’une analyse inter-niveaux, dialectique, des relations entre le monde vécu et son ordre constitué. Il soulève des questions sur les effets de la pratique sur la structure et comment les personnes en action et les contextes sont dialectiquement constitués en relation avec les systèmes sémiotiques et la structuration sociale, politique et économique.

The third mode of analysis is one of interlevel, dialectical relations between an experienced world and its constitutive order. It raises questions concerning the effects of practice on structure, and how persons-acting and contexts (…) are dialectically constituted in relation with semiotic systems and social, political, and economic structuring.

These modes of analysis represent inflection points, the ways in which less-than-wholisticanalyses are likely to take shape in a problematic which configures the encompassing requirements for a complete analysis of practice as they have been laid out here.

à suivre …

Billets précédents

Billet 1: Définitions de l’apprentissage situé

Billet 2: Pourquoi s’intéresser à la théorie de l’apprentissage situé?

Billet 3: Démarche et retour aux sources

Billet 4: Mai 1968 et l’apprentissage situé

Billet 5: Apprentissage situé et conversation

Billet 6: Lucy Suchman, mon téléphone portable et moi

Billet 7: Conversations avec moi-même (n° 1)

Billet 8: L’apprentissage situé mis en pratique, cela ferait quoi?

Billet 9: Contribution de la psychologie soviétique à la théorie de l’apprentissage situé

Billet 10: Les apports de la philosophie à la théorie de l’apprentissage situé

Billet 11: Focus sur l’école Dewey

Billet 12: Apports de la psychologie de la perception – la notion d’affordance

Billet 13: Apprentissage situé et intelligence artificielle, deep learning, réalité virtuelle, réalité augmentée, etc…

Billet 14: Conversations avec moi-même (N°2)

Billet 15: Quand John Dewey rencontre Jean Lave

Billet 16: Cognition in Practice (1/n)

Billet 17: Cognition in Practice (2/n)

Billet 18: Cognition in Practice (3/n)

Billet 19: Cognition in Practice (4/n)

Billet 20 : Cognition in Practice (5/n)

Billet 21: « Conversations avec moi même N°3 »

Billet 22: Cognition in Practice (6/n)

Billet 23: Cognition in Practice (7/n)

Billet 24: Cognition in Practice (8/n)

Billet 25: Cognition in Practice (9/n)

Billet 26: Cognition in Practice (10/n)

Billet 27: Cognition in Practice (11/n)

Billet 28: « Conversations avec moi-même N°4 »

Billet 29: Cognition in Practice (12/n)

Billet 30: Cognition in Practice (13/n)

Billet 31: Cognition in Practice (14/n)

Billet 32: Cognition in Practice (15/n)

Billet 33: Cognition in Practice (16/n)

Billet 34: Cognition in Practice (17/n)

Billet 35: « Conversations avec moi-même N°5 »

Billet 36: Cognition in Practice (18/n)

Billet 37: Cognition in Practice (19/n)

Billet 38: Cognition in Practice (20/n)

Billet 39: Cognition in Practice (21/n)

Billet 40: Cognition in Practice (22/n)

Billet 41: Cognition in Practice (23/n)

Billet 42: « Conversations avec moi-même N°6 »

Billet 43: Cognition in Practice (24/n)

Billet 44: Cognition in Practice (25/n)

Related Posts

Impressions de Cologne

Formateurs, sortez de votre zone de confort!

Qu’attendez-vous?

Articles récents

Archives

- juin 2025

- mars 2025

- novembre 2024

- octobre 2024

- août 2024

- mai 2024

- mars 2024

- janvier 2024

- décembre 2023

- septembre 2023

- juin 2023

- avril 2023

- mars 2023

- janvier 2023

- octobre 2022

- septembre 2022

- juillet 2022

- mai 2022

- avril 2022

- mars 2022

- février 2022

- janvier 2022

- octobre 2021

- août 2021

- juillet 2021

- mai 2021

- février 2021

- juin 2020

- mai 2020

- avril 2020

- février 2020

- janvier 2020

- décembre 2019

- novembre 2019

- octobre 2019

- septembre 2019

- août 2019

- juillet 2019

- mai 2019

- avril 2019

- mars 2019

- février 2019

- janvier 2019

- décembre 2018

- septembre 2018

- août 2018

- juillet 2018

- juin 2018

- mai 2018

- avril 2018

- mars 2018

- février 2018

- janvier 2018

- décembre 2017

- novembre 2017

- octobre 2017

- septembre 2017

- août 2017

- juin 2017

- mai 2017

- avril 2017

- mars 2017

- février 2017

- janvier 2017

Catégories

- Actualités

- Adaptive Learning

- Allemagne

- Apprendre

- Apprentissage

- Branding

- Business

- Coaching

- Codeveloppement

- Communautés de pratique

- Deep learning

- Design

- Development

- E-Learning

- Ecole

- écologie

- Education

- Europe

- Formation

- Histoire

- IA

- Intelligence articificielle

- LBC

- metacognition

- Non classé

- Orientation

- orientation

- Philosophie

- Poésie

- Réalité Augmentée

- Réalité Virtuelle

- Transition digitale

- WOL

Commentaires récents